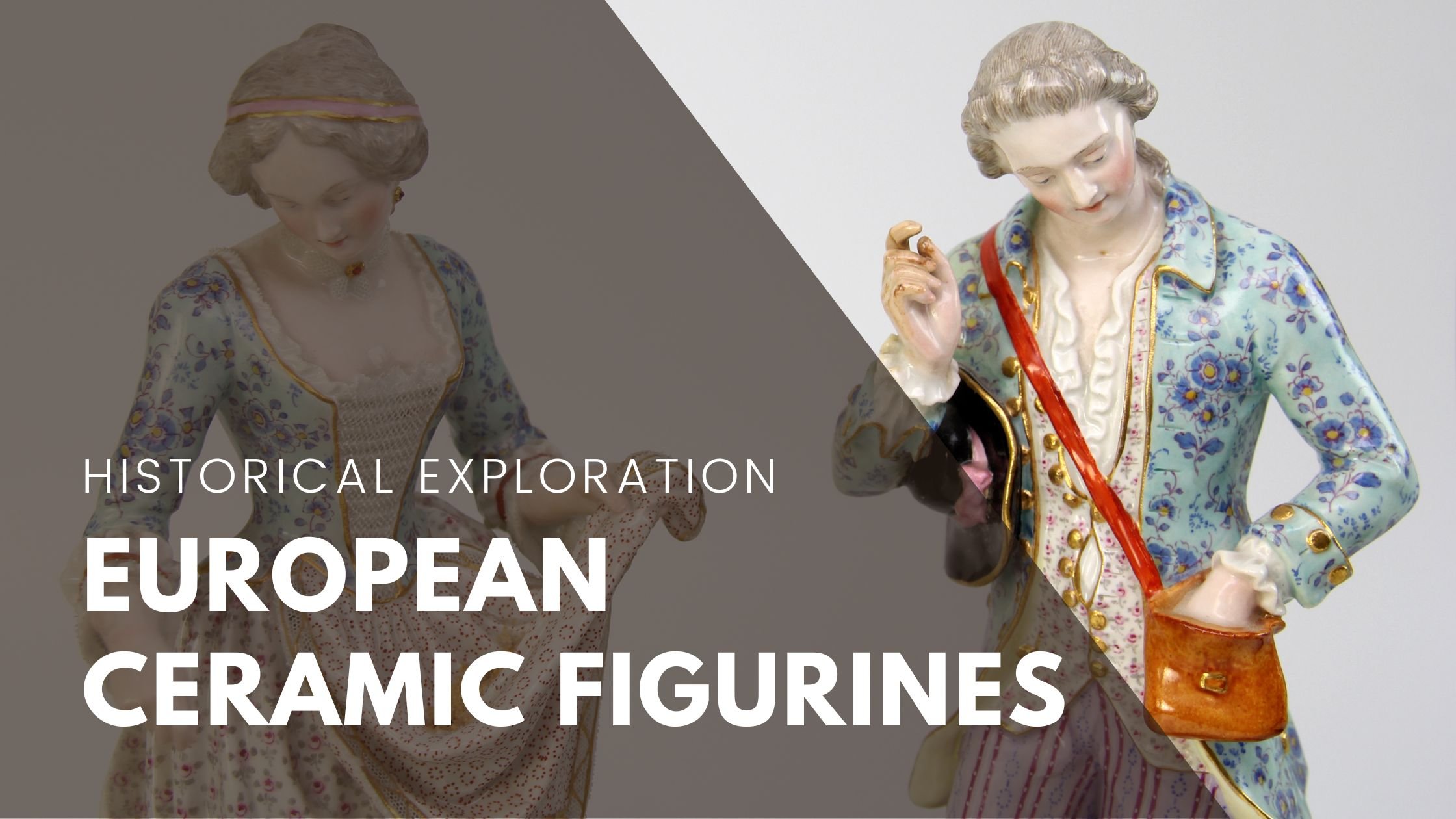

Craftsmanship and Collectibles: A Historical Exploration of Ceramic Figurines of Europe

Origins in the 18th Century

The tradition of creating miniature porcelain figures depicting historical and everyday characters, as well as a variety of animals, originated in the Europe in 1710. Then, Johann Friedrich Böttger, an alchemist from Dresden, discovered the formula for hard-paste porcelain that rivaled that of Asian porcelain. Böttger had already established a faience factory in Dresden, but he moved his porcelain works to Meissen, located nearby along the Elbe River. Meissen remains a prominent hub for earthy art, while Dresden is renowned for its intricate decoration of Meissen porcelain.

Dresden and Meissen figures were renowned for depicting the Italian commedia dell'arte. These colorfully attired actors were expertly crafted by German decorators, with Meissen's Johann Joachim Kändler being the most famous of these early artists. Kändler is credited with inventing the porcelain figurine and creating many iconic characters, including the lustful Pantalone, the lively Columbine, and various mischievous harlequins.

Although Meissen is where European porcelain originated, Dresden is where its decoration was perfected and popularized. Many people mistakenly refer to Meissen porcelain as "Dresden china.” Dresden lace is the most coveted among the many techniques perfected in Dresden. This technique created the illusion of actual fabric on antique figurines of ladies dancing at a court ball or posing in crinoline groups. To achieve this effect, decorators dip delicate lace into porcelain slip before applying it to the figurine. The fabric would burn off during firing, leaving behind a fragile shell of billowy skirts and blouses.

Many ceramists and pottery makers attempted to capitalize on the success of the Germans. One of the most prominent was the Capodimonte porcelain factory in Naples, founded in 1743. They produced soft-paste porcelain imitations of the hard-paste porcelain made in Meissen. Initially, Capodimonte figurines had a shiny white surface that appeared wet. Still, in recent years, the company has shifted towards producing sentimental items such as angel figurines, hobos, and ladies in flowing gowns.

The Staffordshire region of England began using pottery to create beautiful figurines in the 18th century. These figures were initially fashioned of stoneware or earthenware with a salt finish. The English equivalent of pure porcelain, bone china, was eventually adopted by Staffordshire. Companies also produced "chimney ornaments" with a flat surface for wall hanging and freestanding figures.

Commedia dell'arte, a form of theater originating in Italy, inspired the Germans, while images of the British monarchy and rural life influenced Staffordshire artists. Animals from various barnyards and the wild, including cows, horses, sheep, lions, tigers, and elephants, were all represented in their crafts. King Charles Spaniels were also a hot topic, probably due to Queen Victoria's pet, Dash.

One particularly successful Staffordshire pottery, which we know today as Royal Doulton, combined figures with function in its Toby jugs, a popular style of British drinking vessel usually shaped like a standing figure of a man holding a pint (Royal Doulton character jugs, sometimes called mugs, are generally shaped like heads). By the late 1800s, the firm was well known for its large figural pieces in stoneware, some of which stood 20 inches in height. The bone-china pieces were generally shorter, such as the antique figurine of a small boy in pajamas who became known as Darling and was the first numbered figure in the firm's collection.

Around the same time, in 1889, Royal Copenhagen unveiled its first ceramic figurines line of adorable children and cute animals at the Paris World Fair. At the beginning of the 20th century, Royal Copenhagen designers created many of the company’s most enduring collectible figurines, including its beloved family of polar bears.

No doubt the success of these figurines and many others prompted the Goebel pottery company of Germany to approach Berta Hummel, who went by the name Sister Maria Innocentia, about transforming her popular Christmas cards of happy, large-headed, wide-eyed children into three-dimensional pieces. Goebel’s Hummel figurines debuted at the Leipzig Trade Fair in March of 1935, and by the end of the year, they were a source of income for the sister’s convent. But Hummel was no fan of the Nazis, and her artistic opposition to Hitler contributed to her death. Her figures, though, carried on, becoming hugely popular in the United States from the late 1940s through the 1950s and ’60s.

Post-World War II

In the years immediately following World War II, several European and American entrepreneurs got into the collectible figurines game. In Spain, three brothers founded Lladró, initially to make decorative vases and platters but eventually to reprise the porcelain figurines of Meissen and Capodimonte. In the United States, American artists and designers such as Betty Lou Nichols, Hedi Schoop, and Betty Cleminson produced kitschy-and-cute ceramic figurines in small batches from their backyard studios. A few ceramics manufacturers, such as Ceramic Arts Studio (CAS) of Madison, Wisconsin, took more of an assembly-line approach to crank out cats and dogs, boys and girls, and leprechauns by the score.

Japan recovered from the war quickly, though, so it wasn’t long before factories there started supplying U.S. importers like NAPCO and ENESCO with less-expensive versions of the work of Schoop, Nichols, CAS, and others. Of these importers, Lefton China of Chicago, Illinois, whose Miss Priss cookie jars are highly collected, was one of the biggest and arguably the best.

Learn more about Josef Originals including collecting tips here

One postwar American artisan who tried to buck the made-in-Japan trend was Muriel Joseph George, who founded Josef Originals with her husband in 1946. Initially, when confronted in the ’50s by plagiarism of her cute animals and adorable little girls, George tried to add more details to her pieces, but this just made them more expensive. By the end of the 1950s, Josef Originals were made in Japan, which kept the brand competitive throughout the 1960s and ’70s.

While porcelain was the material of choice for most figurine makers, glass was also used. Murano glassblowers made animal figures for hundreds of years, while Steuben had been known for its more sculptural creatures since the 1950s. Still, it was Swarovski who popularized the practice in 1976. That was the year the Austrian firm released its first crystal figurine, a two ½-inch-tall mouse with a length of leather, braided metal, or spring for its tail. Today, Swarovski collectors can choose among thousands of vintage figurines, from alligators to zebras, ballet dancers to Santa Claus. The 1970s were also when Samuel J. Butcher’s devotional Precious Moments cards and posters of children with large heads and teardrop eyes were transformed by Enesco into ceramic Precious Moments figurines.